People often ask me to talk about exact signals in my videos. What shoulder position works? Should I exhale, step back, step forward? How do I stand when my horse won’t settle, won’t move, won’t stop scanning the horizon?

They want the right sequence. The right technique.

And I understand that. It feels reassuring to think that if we just find the correct signal, everything will fall into place.

But the honest answer is: almost every signal depends on context. The age of the horse, the gender, the relationship between you, the emotional state of both of you in that moment, the environment, the season… And – most importantly – the character of the individual you’re with.

A slow exhale that invites one horse into calm might be invisible to another. A shoulder turn that says give me space to a sensitive type might not even register with a bold one who’s already three steps ahead. And sometimes even a clear “no” to personal contact is ignored – despite being one of the most universal signals horses use.

So, technique without character awareness creates friction. Character awareness creates the possibility of alignment.

When I speak about character, I don’t mean personality in a vague sense.

I mean temperament. Nervous system tendencies. How a being processes novelty, pressure, proximity, uncertainty.

Two horses can receive the exact same cue. One relaxes. One escalates. That’s not obedience versus defiance. That’s two different regulatory strategies – and if you’ve ever felt that something should have worked but didn’t, this is usually why.

Communication Begins With Character

When I speak about character, I don’t mean “personality” in a vague, romantic sense. I mean temperament. Nervous system tendencies. How a being processes novelty, pressure, proximity, uncertainty.

Two horses can receive the exact same cue.

One relaxes.

One escalates.

That’s not obedience. That’s regulation style.

Some nervous systems move quickly toward stimulation. Some withdraw. Some intensify emotion. Some shut down. Some seek closeness under stress. Others create distance.

When we interpret all of that as training success or failure, we miss what is actually happening. We are not dealing with stubbornness versus compliance. We are dealing with different regulatory strategies. And if you’ve ever felt that something “should” have worked, but didn’t, this is usually why.

A Practical Way to Talk About Character

Over time, I found it helpful to use the Five Elements framework from Traditional Chinese Medicine as a descriptive lens for temperament.

Not as astrology.

Not as a fixed personality test.

And certainly not as destiny.

And no, I’m not a TCM practitioner 😁. I studied psychology – specifically evolutionary and attachment theory – and I came to typologies with some healthy skepticism. Useful maps, yes. The territory itself? Nope.

No framework captures a whole individual.

And yet.

When I came across the Five Element descriptions applied to horses, something clicked into place.

Not because it was magical, but because it was descriptive in a way that other frameworks hadn’t quite been. It named clusters of behavior I’d been observing but hadn’t grouped into clusters yet. So, the system in the TCM includes basically five character types, but most horses (and people are a mix). We have the five types: Fire, Wood, Earth, Metal and Water. I will say a few more words on the other type later but let me tell you a story about my own mare Cinder and how her character (and ultimately mine) shaped our communication and with that ultimately, our relationship.

A Fiery Story

Cinder came to me as a foal from an auction, initially being from Warm Springs, Oregon – so a former wild horse but only lived wild for 5 months.

Dark, elegant, beautiful.

And absolutely, unmistakably, Cinder would be described in the TCM system as a Fire type.

The Fire type – in this TCM sense – is characterized by emotional intensity, high responsiveness, strong relational needs, and an energy that can tip quickly from brilliant engagement to overwhelm. In horses, this might look like: extreme alertness, hyper-sensitivity to change, difficulty settling in novel environments, a deep need for felt safety before they can trust another’s decisions.

I think I can say, we really got along well. We spend a lot of time together and she always stayed close to me, when I was with her. So that part was never the problem. She was always curious and expressive, and when things were calm, I felt like we had a great connection.

But the moment something shifted in her environment – even slightly – everything changed.

On our walks, if a neighbor had put out their bins since the last time we’d passed, her head would come up.

Body tight.

A sideways dance step.

Snort. Freeze.

And then – the urgent need to be somewhere else, anywhere else, immediately.

If there was a horse she didn’t know in the round pen two properties over, same sequence. She wasn’t being dramatic for effect. She genuinely didn’t feel safe. And because she didn’t trust my decision-making in those moments, she had one strategy: excitement first, then flight.

There’s one walk I still think about. We went past a farm on the way out – quiet, nothing unusual. But on the way back, the farmer had released his cattle. And they’d come right up to the fence to look.

Narrow country road. Ditch on the other side. No space to circle. No way to turn back.

Cinder had never seen a cow in her life.

She was electric.

And I was genuinely frightened – not performing calm, actually frightened – and she could feel every bit of it. I shortened the lead-rope until there was almost nothing left. Moved to the side closest to the cattle, staying as far from the ditch as I reasonably could while still leaving her room if she bolted sideways. And I just walked. Quickly, steadily, forward.

We made it past. It cost me approximately several years of my life. (I’m using that expression loosely, but only slightly.)

Afterwards, I went straight online. Searched for methods. Tried several things over the following weeks and months. Some of them helped a little. None of them helped enough.

I remember standing with her one afternoon and thinking:

Maybe she needs someone else. Someone who can hold a clearer space than I can. Maybe I’m simply not the right person for this horse.

Other people’s horses seemed so much calmer. I’d see them out on hacks, loose-reined, ears flopping, and I’d watch Cinder cataloging every suspicious object within a half-mile radius and wonder what I was missing.

The Shift

The first real relief came when I started reading about Five Element character types.

Not because it gave me a new technique. But because it reframed the whole situation. It wasn’t simply a training failure. It was two temperaments meeting each other– and neither of us having a clear map of what the other needed.

Because here’s the part I’d understood intellectually – but hadn’t yet lived into: I also have strong Fire and Wood character traits: I react quickly. I tend to move fast and think later. I don’t usually respond to uncertainty by becoming deeply Zen. So when something unexpected happened, I wasn’t exactly radiating ancient herd wisdom.

Now, put two sensitive, fast-processing beings together in a tense moment – and you don’t necessarily get calm.

You get amplification.

Her nervous system rose to meet the moment. And mine politely joined it.

So, what Cinder needed wasn’t stricter cues. She needed emotional clarity. She needed someone whose nervous system said: I’ve got this. There is a path through. Follow me – and trust that I know what is dangerous and what is not.

Not performed calm – horses don’t trust performance. They trust the real thing, or they don’t. What they need from us is a quality of presence that’s genuinely grounded, genuinely clear.

Decisive without urgency. Boundaried without force.

I had to become clearer before she could feel safe. That’s not therapy language. It’s relational maturity. It’s what any good herd partner provides.

What It Looks Like Now

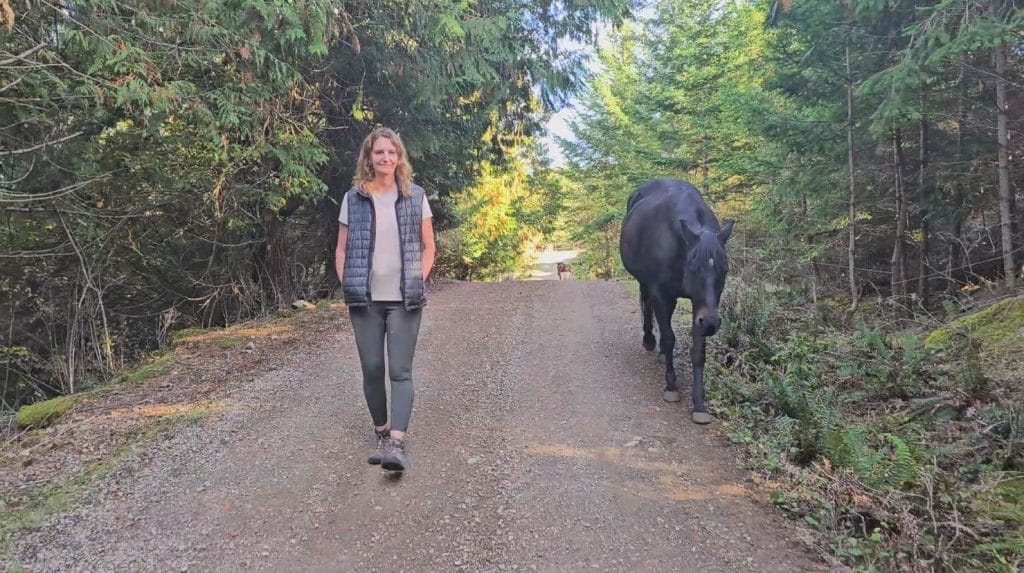

Today, when we go for a walk on our own larger property, I often don’t use a lead rope. I use what I’ve come to think of as a ‘wild-horse-style’ invitation– a particular quality of ‘let’s go’ in my posture and direction – and she joins me about 95% of the time.

Not because she has to. But because she’s curious what I’m up to.

When we go outside the property, I of course use the lead-rope for safety. But I hold it loosely. I walk and trust that she’ll follow, and she does. When something catches her attention, I listen – not blindly, but genuinely. Sometimes her read of the environment is worth considering.

She still reacts. She’s still a Fire type.

But the reaction is different now – contained, not chaotic. She gets activated and then looks to me, rather than deciding unilaterally that we need to leave.

Calm, by her standards. Which is a real thing, and a good one.

A Brief Look at the Other Types

Now, we talked in depth about a fire type, but of course, the Fire character is just one of the five types.

And here are four others, and yes, they all need different things from us to feel safe, seen and connected from us: Wood, Earth, Metal, and Water. And, as I mentioned, most horses are blends of two elements. And yes, of course none of these are strict boxes. They’re just a helpful way to describe patterns of behavior. Tendencies. Clusters that often appear together.

What’s especially important is this: these traits can look very different depending on whether a horse feels emotionally and physically safe — or overwhelmed, stressed, or unsafe.

So here’s a short overview of how these types may show up — especially when something isn’t quite working yet.

🌳 Wood types

They are often labelled stubborn — the horse who plants their feet when there’s no clear direction. But when they’re grounded and confident, that same energy becomes focus and forward drive. So, what they’re actually looking for is purpose. A task with meaning. Something worth committing to.

🌍 Earth Types

Get called clingy or needy — the one who follows you a little too closely and seems unsettled when the group shifts. But when in balance, they’re steady, relational anchors. So, often, they’re simply overwhelmed or carrying too much relational responsibility. And what they need most is steadiness, not distance.

🪙 Metal types

Appear cold or hard to reach — the horse who steps back if something feels inconsistent. But when in balance, they are composed, precise, and very loyal. Metal types are deeply sensitive to integrity. They don’t engage unless something feels clean and true.

💧 Water types

May look shut down or lazy — the one who freezes instead of reacting, scanning quietly before deciding. In balance, however, they are deeply intuitive and emotionally perceptive. But when out of balance, they’re often in quiet hypervigilance, easily overstimulated by what seems minor to others.

In each case, the behavior labelled as “the problem” is usually a stress expression of something that, in balance, is actually a strength. So, understanding character doesn’t excuse us from being clear communicators. But it completely changes how we read what we’re seeing.

If you’d like to read a bit more about the five character types, with examples and practical guidance, you can read the full article here.

What Does This Mean For Us and Our Horse?

Maybe we can stop asking first what exact signal we can use to reach a certain goal– and start asking who our horse really is, and what it needs most from us.

What does their reactivity – or their withdrawal, their pushiness, their shutdown – actually tell us about what’s missing in the relationship?

Not what technique we haven’t tried yet,

but what understanding we haven’t arrived at yet.

The change I experienced with Cinder didn’t come from a better method.

It came from awareness first and then

Consistent presence without agenda.

From working on my own emotional regulation.

From learning to hold clearer limits without raising my energy.

And from accumulating enough relational proof that she could actually trust me in hard moments.

That took time.

There was no shortcut.

Maybe that’s what our horse is quietly asking of us. Less techniques, more observation. Less searching for the right signals, more willingness to see who is actually standing in front of us.

Now, which type sounds most like your horse?

Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water – or some combination that doesn’t fit neatly into any of them? And when you sit with that question honestly, what shifts in how you interpret the things your horse does that frustrate you most?

Behavior that looks like resistance is often temperament meeting an environment that doesn’t yet feel safe.

That’s not a training problem.

It’s an invitation to understand more deeply.

And wild horses taught me this, slowly and clearly: the one who earns trust isn’t the most skilled, or the most firm, or the most patient in isolation. It’s the one who truly knows who they’re with.

And knowing who you’re with means understanding more than just the signals. It means understanding what shapes how those signals land – character, age, sex, relationship history, emotional state, environment. All of it, together, in every single interaction.

That’s what we explore in Being Herd. Not a list of techniques to apply – but a way of reading the whole picture. The wild horse world gives us the clearest possible reference point for this, because out there, nothing is abstract. Every signal has context. Every response has a reason. And the horses who navigate it best aren’t the ones who know the most moves. They’re the ones who read the situation – and the individual – most accurately.

If that’s the kind of understanding you’re looking for, you’ll find the details here.

Recent Comments