If you spend time around horses, you hear these words everywhere: dominance, hierarchy, rank. One horse is dominant at the hay. Another is low in rank. A horse resists and is said to be “testing” their human.

These ideas are so common we rarely stop to question them.

The issue isn’t the words themselves

is what we usually mean when we use them.

When many people talk about hierarchy in horses, they imagine a fixed internal order. A clear line. Who moves first, who gives way, who gets access to food or space, and who doesn’t. A structure where some horses are consistently “above” others, and where control over resources defines social position.

That picture sounds logical. It even sounds natural.

But when you start observing horses living in stable social groups, something doesn’t quite add up.

So instead of arguing against these ideas, I’d like to invite you to look a little closer with me. Not at training methods or problem behaviours yet, but at the social structure. At how horses actually organise their lives when they are free to do so, and what changes once we bring them into domestic settings.

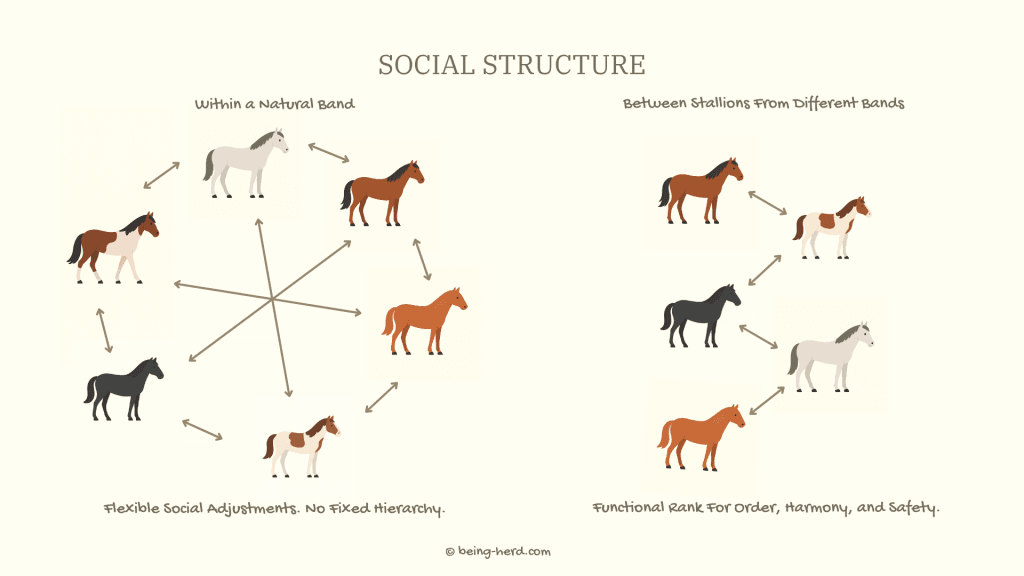

To do that, we need to separate three different levels that often get mixed together:

- what happens inside a natural band

- what happens between different bands

- and what this means in our everyday life with domestic horses, both in their social groups and in their relationship with us

Once we look at these situations separately, many things that look like dominance start to make a lot more sense.

1. Inside a Natural Band: A Dance, Not a Domination

If you watch a real wild band that’s lived together for years, one thing stands out right away: what you don’t see.

There is no visible internal hierarchy in the way we often imagine it.

No fixed order.

No horse that consistently controls the others.

No clear “top” and “bottom” that defines daily life.

Inside a natural band, horses do not live by a stable ranking system that determines who may access resources first or who must always give way. There is no permanent line that everyone silently follows. Instead, social life is shaped moment by moment.

Horses adjust to each other constantly. They give space, take space, change positions, and move again. What happens depends on proximity, relationships, current needs, and the emotional state of the horses involved. The same horse may step aside in one moment and hold its ground in the next, without this saying anything about rank or status.

What you see instead is this:

- Horses adjust their distance to each other

- They negotiate space calmly

- They respect each other’s personal comfort zones

- They move together because they want to stay safe and connected

- They sort out small conflicts in seconds and return to harmony immediately

What happens depends on context: proximity, relationships, current needs, and emotional state. The same horse may step aside in one moment and hold its ground in the next, without this saying anything about rank or status.

So, if hierarchy means a fixed internal ranking, you won’t find that inside a natural band.

Here’s a simple example: Two horses are resting close together. A third approaches and signals a wish to stand in that exact spot. One horse moves a few steps away. Later that day, the roles reverse. There is no rule being enforced, no score being kept, no winner and loser.

Just a brief negotiation.

A clear signal.

A quiet response.

And then: calm again.

Tension appears, is communicated, and dissolves within seconds. Horses return to grazing, resting, or moving together, often in synchrony. This rhythm of tension, adjustment, and release is normal social life for them.

And it makes sense:

- it keeps the band cohesive

- it avoids unnecessary conflict

- it allows everyone to stay relaxed and attentive

- it supports shared safety in an open landscape

For a prey species, flexibility is more useful than force. Fluidity works better than fixed order.

So when we look at the internal structure of a natural band, we don’t see domination. We don’t see rank governing everyday interactions. What exists is a constant dance of small adjustments, shaped by relationships, mood, proximity, and trust.

This is the baseline of horse social life.

2. Between Bands: Where Rank Actually Belongs

After looking at life inside a natural band, there is one important question left.

If horses don’t organize their daily social life through rank internally, where does the idea of hierarchy come from?

The answer is found outside the band.

When several bands share the same landscape, we enter a very different social situation. Here, horses are no longer regulating closeness within a familiar group. They are coordinating movement, access, and safety between independent social units.

This is where rank becomes relevant.

And it’s the only place where it actually matters.

Between bands, the primary point of orientation is each band’s stallion. These stallions form a functional order among themselves. Not to dominate others, but to create order and harmony in situations where many horses move around or through the same space.

These situations are specific and limited to certain moments. For example:

- access to water

- eating at their favorite apple tree

- narrow paths during migration

- open terrain during flight from danger

In such contexts, it matters who moves first. It matters who takes position where. It matters who defends which boundary. Not because they want power, but because it keeps the large social system organized and reduces chaos during critical situations.

So, it is important to understand what this rank is not.

It is not a reflection of personality.

It is not about control.

It is not a model for daily social life.

It is a coordination tool.

Stallions negotiate this order through ritualized displays, posture, presence, and sometimes brief physical encounters. Serious fights are rare and usually only occur when the stakes are high. And even then, the goal is not victory, but resolution.

Once established, this order reduces tension for everyone involved. Bands can share a landscape for years, even decades, because boundaries and expectations are clear.

This brings us to an important distinction.

This rank does not describe how horses live with their band.

It describes how bands live next to each other.

Or put more clearly:

This is the only context where rank has real meaning in horse society.

And it does not describe daily social life inside a band.

Keeping this distinction in mind changes everything. It prevents us from projecting a between-bands concept onto situations where it does not belong. And it helps us understand why so much of what we label as dominance later on feels confusing, inconsistent, or simply wrong.

With that in mind, we can now return home. And look at what happens when domestic horses live in conditions that mix these two very different social layers.

3. Where the Misunderstanding Begins: Our Horses

So far, we’ve been talking about wild horses in natural social systems. Now, we come back home. To our own horses. And this is where misunderstandings often begin.

In domestic settings, we often see behaviors that look anything but calm and fluid. Horses chase each other away from hay. They pin their ears at gates. They guard space. They push. They get pushed. And very quickly, these moments are labeled as dominance.

It’s understandable. From the outside, it looks like someone is trying to control access or establish a higher position.

But this is where things start to blur.

What we are seeing here is not the internal social structure of a natural band. It’s not hierarchy in the sense of rank. And it’s not a stable social order being played out.

What we are usually seeing are coping strategies.

Domestic horses live under conditions that are fundamentally different from those of wild bands. Their groups are often artificial. Space is limited. Resources are concentrated. Movement is restricted. Escape options are few. Social histories are mixed. Some horses have known abundance, others scarcity. Some grew up in stable groups, others in isolation.

Under these conditions, horses do what all social animals do under pressure: they adapt.

A horse that repeatedly drives others away from the hay is not “high-ranking” in a natural sense. It is stressed. It may be insecure. It may have learned that access to food is uncertain. Another horse that consistently retreats is not “low-ranking”. It may be conflict-avoidant, younger, less experienced, or simply naturally quieter.

This is not hierarchy.

This is context shaping behavior.

The same applies when horses seem to “resist” humans. What looks like a challenge to authority is very often a response to pressure, confusion, discomfort, or lack of safety. Again, not a rank question, but a situational one.

Yes, it looks like “dominance”, but only because we don’t yet have a better framework.

And this is why it’s worth to pause here before jumping to solutions. Because if we misread these behaviors as expressions of hierarchy or rank, we end up trying to fix the wrong problem. We correct or limit the horse, when in reality, it’s the situation that needs attention.

To understand what our horses are actually doing with each other, we need to step out of the dominance lens. We need to look at how horses organize access and reduce stress when their environment doesn’t allow the kind of social fluidity we see in natural bands.

4. What We See in Domestic Groups Instead

When we leave the wild and look at domestic groups, the question is no longer about hierarchy or rank. It’s about how horses cope with the conditions we place them in.

Domestic groups are not wrong or “unnatural” in a moral sense. But they are different. And those differences matter. When space is limited, resources are concentrated, and movement is restricted, horses can no longer rely on the same fluid social adjustments that work so well in natural bands.

So instead of asking who is dominant, a more helpful question is:

What kind of system are these horses trying to make work?

4.1 A Context-Dependent Priority Strategy

When horses live under pressure, they begin to organize access instead of relationships.

This is what I describe as a context-dependent priority strategy.

It is not a social structure.

It is not hierarchy.

And it is not how horses prefer to live.

It is what they do when they have to.

Three things define this strategy.

First, it depends on the environment.

If there is enough space, enough forage, and enough freedom to move, these behaviors often soften or disappear entirely.

Second, it is flexible, not stable.

A horse that pushes others away one year may step back the next. Age, pain, confidence, social learning, and experience all play a role. Nothing about this is fixed.

Third, it is about stress and survival, not status.

When two horses compete for the same limited resource, the one with more urgency, confidence, or need in that moment gains access.

This does not create rank. It resolves pressure.

In everyday language, this could be called a stress-based priority order. It makes clear that the pattern is created by circumstances, not by a horse’s character or social ambition.

Seen this way, many behaviors that look like dominance begin to make sense. They are adaptive responses to a system that does not allow enough flexibility.

4.2 When Domestic Groups Behave Like Separate Bands

There is one more pattern that matters. It is less common, but important.

Sometimes domestic groups do not function as a single, integrated social unit. Instead, they behave like two separate bands sharing the same space.

This is the only situation in domestic keeping where rank-like behaviour between horses can actually appear.

Here, we may see posturing, driving, or short but genuine ranking conflicts. Not because horses are trying to dominate their own group, but because two distinct social identities are negotiating contact, much like wild bands do at shared resources.

What matters is this: sometimes these groups integrate over time, and the tension dissolves. And sometimes, even under very good conditions, they don’t.

This is not a failure.

It is a natural social preference.

As long as there is enough space, clarity, and access to resources, two non-integrated groups can coexist peacefully. The key is understanding why tension appears in the first place:

- Is there a lack of resources? (easy to fix)

- Is this a temporary negotiation between new subgroups?

- Or are these two stable groups that simply don’t want to merge?

Misreading this situation as a dominance problem often creates more stress than it solves.

4.3 What This Means for How We Keep Horses

Once we see these patterns more clearly, many situations feel less dramatic – and much more solvable.

What often appears as “dominance” in domestic groups is, in reality, a sign that the current set-up asks too much of the horses. Not because anyone did something wrong, but because the conditions make flexible social behaviour difficult.

So, once we shift our focus from rank to conditions, we can support the horses by asking questions like:

- Is the group composition stable?

- Is there enough space to avoid each other?

- Are feeding stations designed to allow distance?

- Can horses move freely throughout the day?

- What social experiences do they bring with them?

- Are age, pain, or physical limitations influencing behaviour?

And in the cases where tension persists, it can be helpful to have someone with a trained eye look at the group as a whole. Not to assign blame or labels, but to understand whether the underlying cause lies in stress, resource pressure, personality mismatch, or a stable dual-band structure that simply needs different management.

5. What This Means for Our Relationship With Horses

Once we understand how horses organise themselves socially, the relationship side follows almost naturally:

We’ve just seen that inside a band, horses do not dominate each other to create belonging. Dominant behavior, in a social sense, actually signals separation. It says: you are not part of my group.

This doesn’t mean we can’t be clear, set boundaries, or express our own needs. We absolutely have to. But using dominance as a relationship framework in the sense of “I always tell you what to do because I am the alpha” tells the horse that we stand outside their social world, not within it.

And this is why relationship problems cannot be solved through “being the boss” or asserting rank. When we try to fix connection through dominance, we often create the opposite of what we’re hoping for. Instead of safety and trust, we create distance, obedience, and maybe even fear.

So, if we want our horse to experience us as part of their social world, it makes sense to behave in ways that mirror how horses relate within a band: through clarity, consistency, collaboration, calm presence, and respect for signals.

Not force.

Not pressure.

Not hierarchy.

6. Closing: What Horses Are Really Doing

Horses aren’t trying to win.

They’re not trying to control others.

And they’re certainly not trying to climb a social ladder.

Wild horses don’t fight for power.

Domestic horses don’t fight for status.

What they do instead is much simpler. They use small, practical strategies to stay safe, stay fed, and stay calm within the conditions they find themselves in.

Once we start seeing it this way, something changes. We stop asking who is dominant and begin asking what is this environment asking of the horse. We stop correcting behaviour in isolation and start looking at the conditions that shape it.

The old dominance framework was always too blunt for horses. It forces a fluid, sensitive social world into a rigid model that doesn’t match how horses actually live or relate.

Wild horses show us flexibility and adjustment within the band. Between bands, stallions show functional rank when coordination and safety require it. And domestic horses show us just how adaptable they are, even when the system makes things difficult.

Every horse carries a natural capacity for cooperation. Our role isn’t to control it or override it, but to create the conditions where it can surface on its own. When we do that, life with horses tends to get quieter. Clearer. And more honest – both in our herds and in our relationships with them.

And if this way of seeing horses feels right to you, you’re invited to explore it more deeply inside my Being Herd Program. There you’ll find weekly videos, in-depth Deep Dives, practical tools, and personal support to help you understand your horse even better. Everything I share is grounded in real wild horse behavior and what it teaches us about connection.

💛 Or start by downloading my free guide here

Your horse already carries this kind of relational intelligence.

They use it every day.

And when you start seeing them through this lens, something shifts – for both of you.

Thanks for reading, and for choosing a path that supports your horse and yourself.

Recent Comments