I keep hearing or reading the same sentence in my comment section again and again: “Stallions kill foals that are not theirs. That’s a strategy to make sure only their genes get passed on.”

It sounds like settled science. Like a fact everyone agrees on. Like something we no longer need to question.

But this statement usually turns very different situations into one single story. So before we even discuss whether stallions kill foals and why, we need to be clear about what we are actually talking about.

1. Define the Situation – Or We Talk Past Each Other

When people say, “stallions kill foals,” they often mean very different things without realizing it. Different species. Different social systems. Different situations. Different causes of death. All of that gets compressed into one claim. So, in this article, I am *not* talking about zebras, lions, primates, or “mammals in general.”

I am talking about horses. And more precisely, wild and free-living horse bands with natural social structures.

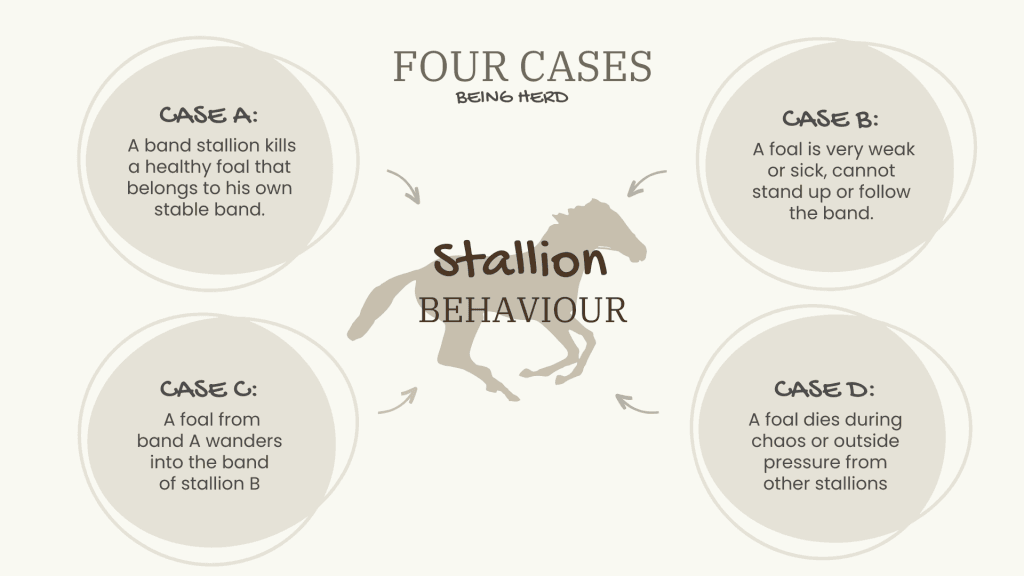

And when we talk about “stallions killing foals”, we need to separate four very different cases:

**Case A:** A band stallion kills a healthy foal that belongs to his own stable band.

**Case B:** A foal is very weak or sick, cannot stand up or follow the band.

**Case C:** A foal from band A wanders into the band of stallion B.

**Case D:** A foal dies during chaos or outside pressure from other stallions.

These cases are not the same biologically, socially, or logically.

My claim in this article refers only to Case A.

I am not saying that foals never die, that stallions never attack, or that wildlife is gentle. I am saying something much more specific:

In natural, stable wild horse bands, stallions do not kill healthy foals that belong to their own band. They protect them.

That sentence contains several important limits. I am talking about:

- Natural or free-living herds, not captivity or forced groupings

- The band stallion, not a foreign stallion or bachelor

- Healthy foals, not weak, sick, or immobile ones

- Foals that clearly belong to that band, not foals caught between groups

Most discussions about “infanticide” never specify any of this. They simply say “stallions kill foals” as if that were one clearly defined behavior. It isn’t.

My position is not based on feelings or on wanting stallions to look good. It is based on one simple observation: when you look at what actually happens in stable wild horse herds, stallions protect foals. That is the pattern.

Foals may die for many reasons. But targeted killing of healthy foals by their own band stallion does not appear as a normal or functional strategy in horse societies.

So, this article is not about winning an argument. It is about being precise about what we mean when we talk about horse behavior.

2. Testing the Infanticide Argument

People who argue that stallions kill foals usually rely on four main explanations:

- Gene spreading – the stallion kills the foal so the mare becomes fertile again sooner

- Resource management – an unrelated foal is a waste of time and energy

- Competition elimination – male foals are future rivals that should be removed early

- Paternity control – the stallion recognizes that the foal is not his and acts accordingly

For any of these to work, one condition must come first: the stallion would have to know with certainty that the foal is not his. So let’s start there.

Claim 4: Paternity Control

How would a stallion know a foal is not his? There are only two possible situations.

First, the foal is born inside his band.

In that case, what would tell him? Does he calculate conception dates? Does he smell the foal and detect genetic identity?

None of this makes biological sense. Even mares and foals, who are clearly related, need time after birth to recognize each other by smell and behavior. The idea that a stallion can instantly and reliably detect paternity at birth is an assumption, not a demonstrated ability. And if he were wrong, the cost would be catastrophic. He would be killing his own genetic offspring.

Second, a mare arrives with a foal from another band.

In that case, yes, the stallion can be fairly sure he is not the father. But then a different question appears: if his first action is to kill her foal, why would she stay?

Mares choose stallions largely for protection and stability. A stallion who kills foals would be the worst possible partner. A behavior that drives mares away cannot function as a successful reproductive strategy in a species where herds are formed by voluntary association.

Claim 1: Gene Spreading and Heat Cycles

This argument assumes that killing the foal would significantly speed up reproduction.

But in horses, mares come into foal heat very soon after giving birth anyway. The stallion can mate with her regardless of whether the foal is alive or not. Killing the foal does not meaningfully change the reproductive timeline.

What it does change is the mare’s willingness to stay. A stallion who threatens her foal risks losing her entirely. From a reproductive standpoint, that is not an advantage. It is a liability.

Claim 2: Unrelated Foals Are a Bad Investment

This claim assumes that foals are a burden.

But stallions are built to guard herds. Guarding is their role, whether foals are present or not. Some stallions even protect bands as lieutenants without breeding a single mare. So, protection is not something they only offer to their own genetic offspring.

And foals are not a cost to a herd. They are an asset. Fillies may later become band members. Young males help with group cohesion and defense before they leave. More individuals increase safety and stability. A band with foals is more attractive to mares, not less.

From an evolutionary perspective, what actually increases a stallion’s reproductive success is keeping his band stable and appealing. A stallion who protects all foals is advertising: this is a safe place to raise young. That is the real advantage.

Claim 3: Male Foals as Future Rivals

This argument assumes long-term strategic planning: killing a newborn today to prevent competition years later.

But stallions do not need to solve future competition by killing babies. Young males are simply driven out when they become a real social or sexual challenge. And that happens later, through social pressure, not through foal killing.

And we see something that directly contradicts this idea: band stallions often interact peacefully with youngsters from other bands. They tolerate them, play with them, and allow them to be close. Just like band stallion Reece playing here with 10-month-old Fox from a different band:

So, if stallions were biologically driven to eliminate future rivals, these interactions would be extremely risky. Yet they happen regularly.

What This Tells Us

When these four claims are tested against how horse societies actually function, they rely on an unproven ability to detect paternity, a model of mares as passive property, and a social system that does not match horse reality. The infanticide theory may work for other species. But it does not fit horses living in stable herds.

So: death alone does not prove intention. Pressure, movement, weakness, and chaos can all lead to fatal outcomes without any goal to kill a foal. Outcome and motive must be separated. A dead foal does not automatically mean infanticide.

3. What Really Happens When Foals Die

When people say “stallions kill foals,” they usually imagine a deliberate act with a clear reproductive goal. But when you look at real situations in wild herds, foal deaths almost never look like that. What you see instead are combinations of pressure, fast movement, and vulnerability.

Bachelor pressure is one common situation. Bachelor stallions approach a band because they are interested in the mare, not the foal. The mare tries to stay with her band. The bachelor tries to pull her away. The herd stallion tries to keep his group together. This creates fast movement, sharp turns, and repeated chases. In that chaos, a very young foal can fall behind, get knocked over, or become separated.

Weak or compromised foals create another kind of danger. A foal that cannot stand, cannot follow the herd, or cannot keep up creates a dangerous situation for the entire group. The mare usually refuses to leave it while it is still alive. A weak foal increases predator risk and forces repeated stressful movement. What looks like aggression is usually part of a breakdown in movement and safety.

Boundary crossings between bands can also be fatal. Young foals can be surprisingly mobile, which is why one of the first lessons they learn is to stay with their band. This rule is enforced with clear signals by both the mare and the band stallion.

If you want to see a real example of this kind of situation, I explain one such scene step by step in my YouTube video here.

Still, sometimes a foal ends up near a foreign group while its own band is grazing at a distance. When this happens, a stallion from another band may react defensively or aggressively to the intrusion. In rare cases, a foal may be injured or killed.

And finally, artificial or human-created conditions – small enclosures, forced groupings, lack of escape routes, sudden removals or reunifications – create social situations that do not exist in natural herds. Behavior observed under those conditions cannot be used as evidence for what normally happens in free-living horse societies.

And all of these situations still get framed as “a stallion killed a foal,” contributing to the idea that this is a common strategy because it is widely shared on social media.

At the same time, what we rarely see documented are the countless calm interactions: stallions standing guard while foals rest or positioning themselves between foals and danger. We also see them allowing foals from other bands to graze nearby, like band stallion Moondrinker here with a foal that belongs to a different band, Sunstar’s:

So, across all of these situations, one pattern remains consistent: foals die in moments of instability, pressure, or weakness. What we do not see as a stable pattern is a herd stallion deliberately killing a healthy foal that belongs to his own band.

4. A Real Example: How Stories Are Born

Now let’s look at how these ideas – or misconceptions – about herd behavior and stallions killing foals are actually created. We are talking about one scene that circulates widely online. It is always the same footage. But there are at least three very different interpretations of it. And the question is: which one is actually supported by what we see?

Let’s start with the first interpretation.

Interpretation 1

The title of this video is: “This foal was attacked by his own herd, but his mother wouldn’t allow it.”

So the story becomes: the band wanted to kill the foal, even though it supposedly belonged to the same band.

The narrator then adds that the mother “wouldn’t allow it” because she somehow knew what the foal was capable of. It is never explained what that is supposed to mean.

The reason given for why the “own band” attacked the foal is that it smelled strange and therefore was not accepted by the others. Then other clips – which are not related to the initial scene – are added and more dramatic explanations are layered on top.

This video has more than 100,000 likes and almost 3,000 comments.

So what do you think all these people now believe about horses? They believe that bands kill their own foals. They believe that smell decides whether a foal is allowed to live. And they believe that this is normal herd behavior. All of that comes from one short scene plus a story told over it.

Now let’s look at the second interpretation.

Interpretation 2

Now the narrator says a group of “stallions” appeared to claim the mare. That is at least one step closer to reality, because yes, the males in the scene do not belong to her band.

But then the narrator adds: “First they needed to kill her newborn.”

From that point on, the whole scene is narrated as if killing the foal is the goal. Everything is framed in the most dramatic way possible.

The result: almost 430,000 likes and about 1,600 comments. So clearly, this version worked even better. Not because it explains the behavior more accurately. But because it tells a more shocking story.

Now let’s look at the third interpretation.

Interpretation 3

This version finally shows what is actually happening.

The mare is trying to protect her foal while bachelor stallions approach her. Their main goal is not the foal. Their goal is the mare. They are trying to get her to move with them, away from her band.

Is that dangerous for the foal? Yes, absolutely. In that chaos, the foal could get injured or even killed. But it is not the target. And this point is crucial.

This chaos does not happen because the stallions want to kill the foal. It happens because bachelor stallions are trying to separate a mare from her band.

Of course, in that situation, a very young foal can fall, get separated, or be trampled. But that is a tragic risk of movement and pressure – not a planned act of infanticide.

And this distinction matters. Because if we do not separate “band members” from “bachelors creating chaos,” or “healthy foals” from “weak foals under pressure,” then we end up explaining completely different situations with the same word.

And that is exactly how myths are born. One scene. One dramatic narration. And suddenly it becomes “biological truth.” Not because the behavior supports it. But because the story is easier to believe than the context.

5. Stallions Adopting and Protecting Foals

What is interesting is not only what people think they see, but also what is rarely shown. Videos of stallions protecting foals, standing over them, or allowing foals from other mares to stay close are far less dramatic and therefore far less likely to go viral. But they exist, and they matter.

There are many documented cases where stallions interact gently with foals, invite them to play, or position themselves between foals and potential danger.

Just like band stallion Spartan (on the right) here resting with his stepson Caspian right in front of him:

There are even cases where a stallion takes over the care of a foal when the mare is absent or dies, staying close to it and defending it against other horses.

These scenes do not fit the infanticide story, so they are often ignored. But they are just as real as the dramatic clips of conflict.

The existence of these counterexamples does not mean that nothing bad ever happens. It means that the idea of stallions as default foal killers does not match the broader pattern of their behavior. A theory that explains only the most extreme scenes but fails to explain calm, cooperative ones is not a good theory.

When you put the two together, a much more consistent picture emerges. Foals are safest in stable herds with clear boundaries and experienced adults. They are most at risk when herds are under pressure, when boundaries break down, and when movement becomes chaotic. Stallions, especially herd stallions, are usually part of the protective structure, not the threat.

6. Conclusion – and an Open Invitation

After separating the different situations, looking at what actually happens in wild herds, and testing the usual explanations against horse social reality, one pattern becomes clear: in stable, natural horse herds, herd stallions are consistently observed protecting foals, not targeting them.

What we sometimes do see are deaths connected to chaos, weakness, or intrusion. These are tragic outcomes, but they are not the same as a deliberate reproductive strategy.

There is one study that shows how a new band stallion indeed tried to attack a foal within his own band. But the mare was able to defend the foal, and it grew up happy and healthy. But why do you think they published that moment as a study? Not because it is common. Because even the researchers were surprised. And the scene didn’t end in a killing.

So, yes, sometimes very unusual things happen when stallions are overwhelmed, confused, or focused on something else. But it is not a common strategy. It’s a rare exception.

We should be careful not to turn every foal death into a story about intention. A dead foal does not automatically mean infanticide. A dramatic scene does not automatically reveal a biological strategy. And a theory borrowed from other species does not automatically fit horses.

What matters is pattern, not exception. What matters is context, not headlines.

That is why I want to end this article with something very concrete and very honest.

If you have material that clearly shows the following situation, I want to see it: a stable wild horse herd, a clearly established band stallion, a healthy foal from a mare that clearly belongs to that band, and a targeted killing of that foal by that stallion.

Not zebras. Not captivity. Not a bachelor attack. Not a sick foal. Not a foal caught between bands. A real, natural band and a real, healthy foal.

If such material exists, it should be part of this discussion. It should even be published in the scientific realm. Because this is not about defending stallions. It is about understanding horses.

Until then, the simplest explanation remains the most consistent one. In horse societies, foals are part of the social fabric. Herd stability depends on them. And stallions, far from being programmed to destroy them, are usually part of the structure that keeps them safe.

Not because stallions are kind. But because horse societies only work when young animals survive.

And that, in the end, is the strongest argument of all.

If you’d like you can also watch the full YouTube video version of this topic here, where I walk through real footage of a stallion attacking a foal and show how these situations are usually misinterpreted.

And if you’d like to explore even more real-life examples and discover how wild horse behavior translates to our domestic horses, I’d like to invite you to join my video library or start with my free guide.

Recent Comments